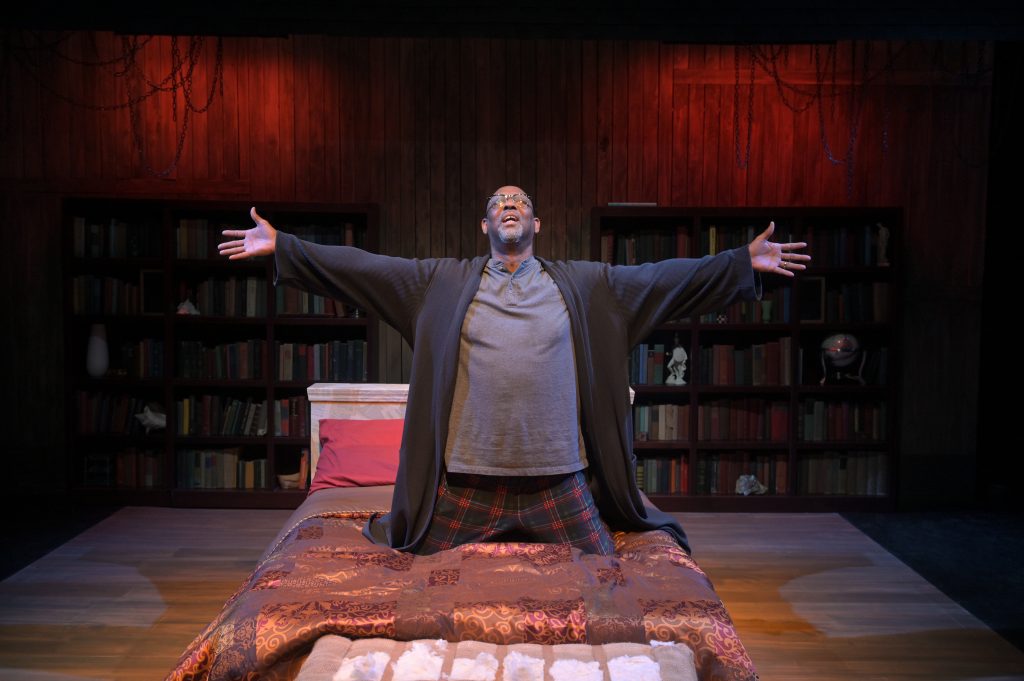

Lewis, the central character in Tanya Barfield’s Blue Door, is a middle-aged Black mathematics professor struggling with his sense of identity and heritage. Feeling disconnected from his African American heritage and deep personal conflict around his social-cultural identity, Lewis is visited by some spirits of his ancestors. Lewis grapples with the legacy of his family’s history, particularly the stories of his ancestors’ struggles against enslavement, racism, and oppression. This internal dilemma is exacerbated by the pressure to conform to societal expectations of what it means to be a successful Black man in America. Lewis’s journey in Blue Door is a deeply personal exploration of race, memory, and the complex interplay between individual identity and collective history. As he confronts his past and wrestles with his own demons, Lewis undergoes a profound transformation, ultimately finding a deeper understanding of himself and his place in the world.

When writing the play, Tanya Barfield says that Simon emerged for her first, and the question she asked was, “Who needs to hear from Simon?” That is how Lewis came to be. Lewis, who spent his life concerned with upward social mobility and respectability politics, left behind blood memory and ancestral veneration as a way of knowing. When asked about invoking the ancestors in this play, Michael says, “I know who is with me when I perform this play.” He even goes so far as to pay homage to his own late brother through some subtle choices in costume design. The metaphorical blue door ties Lewis’s present reality to the spiritual realm. In many African and Black American spiritual traditions, the color blue is believed to have protective qualities, warding off evil spirits and negative energy, so a blue door is thought to bring protection from haunts or malevolent spirits to the home and those residing within. Michael claims to feel only love and joy in the presence of his ancestors.

Where Michael and Lewis align is inside the academy, walking the halls of predominantly white institutions (PWI). While Lewis saw academic prowess as a means toward equality, Michael grew up with hoop dreams like so many other urban youths. Michael’s father insisted that education be a top priority and enrolled him in college prep courses starting in junior high school. College was imperative in his household, and consequently, Michael was a powerhouse athlete who soared academically. Michael attended the University of Washington in the 1980s, and when asked if he had any Black professors, he says, “Yes, none of them were Lewis.” Michael was exposed to Black professors in Black Studies classes as part of UW’s American Ethnic Studies program. “It was in Seattle, at UW, that I met Bobby Seale. And Jesse Jackson,” he shares. While Lewis leaned into assimilation through the academy, Michael’s racial identity was affirmed through consciousness-raising coursework and events. He even contributed to the BPP free breakfast program when he was a student, he says, “because the Brothers were on campus soliciting donations.” When asked about the Million Man March in 1995, Michael says he “knew about the march. I was supportive of the march. It wasn’t on my mind to go, though, because I was in single-parent daddy mode raising a family at that time.”

With such divergent backgrounds, it may be curious how Michael can play the role of Lewis with such conviction. Michael says, “The older I get, the more I understand. When I was a teenager, my father moved to Bremerton, WA, and I was like, Bremerton? Now I understand. He wanted peace of mind, to feel safe. That’s hard to find right now in the bay.” Michael has compassion for Lewis and all Black men. For him, he has been able to define success for himself, but he recognizes that some Black men are subject to circumstances beyond their control, quoting the adage, “You can’t win, you can’t break even, and you can’t get out of the game.” On this law of thermodynamics, Lewis and Michael likely agree. “This is a special play with an important message,” Michael says. He adds that “playing Lewis is a gift. Having theatres like Aurora continue to produce plays with roles written specifically for Black men–I mean, Shakespeare is fine, but August Wilson, that’s my dude–I never dreamed of performing these roles when I was a young man. I’m not Lewis, but I know Lewis. I get Lewis.”

– Dawn Monique Williams